“Old Woman Eating” by Quiringh Van Brekelenkam (Google Art Project)

Leah Wilkinson was described as a ‘notorious old offender’ by the Navy in 1712. She had a long career as a forger and con-woman – with known criminal offences being committed over a 30 year duration. She made a living by forging wills and letters of attorney for seamen, and was able to carry on this criminal career because of her powers of persuasion and language, undeterred by spells on the pillory.

Although biographical details for Leah are few, from my research, it looks like she was born Leah Lowe into a Quaker family in London. She married Samuel Wilkinson in 1688, and they had at least one son.

The first time Leah is recorded as appearing at the Old Bailey is on 3 December 1695. She was accused of forging seven letter of attorney and wills, purporting to have been written by various seamen. By forging these documents, she had managed to obtain £200 – around £16,000 or £17,000 in today’s money. She was lucky on this occasion, being acquitted by the court – not because she was found to be innocent, but because there was a mistake in the written indictment of her charge, and so the case could not go ahead [1].

Seamen were targeted by Leah because they were able to appoint attorneys to receive their pay in their absence. These letters of attorney could therefore be forged by those hoping to obtain the seamen’s wages – with them at sea, they would not learn of the deception for some time.

Another way to get money – as Leah did – was to add a clause to the letter of attorney, purporting to be a will made by the seamen, whereby ‘they make their attorneys their executors and give the whole estate or great part thereof, the seamen being ignorant’. [2] If the seaman did then die at sea, his relations could end up penniless as a result of these forgeries.

Leah didn’t appear before the Old Bailey again until 1727 – but this does not mean she lived a virtuous life until then. She appears in other records, and was clearly up to her old tricks. In fact, she even forged a letter of attorney from her own mother.

In April 1696, Edward Whitaker wrote to the Navy Board on behalf of John King, a scrivener. King’s job was to make letters of attorney for seamen, but the Navy Board had ordered that ‘no such letters made by him will be looked on as good’ any more. This was as a result of having been paid to forge a letter of attorney for Anne Lowe – Leah’s mother, who had died in 1694. However, Whitaker noted, although King admitted the offence, he had never been prosecuted for the offence – and, ‘as he could be useful’, Whitaker recommended the Navy Board re-employ him. [3]

But Whitaker was clearly aware of Leah Wilkinson’s involvement in this offence. Two months later, in June 1696, he again wrote to the Navy Board, detailing forged documents supposedly from three people – a Captain Leake, former commander of the Sally Rose ship; Katherine Lovelace; and one Anne Lowe, deceased. This offence involved money being charged on ‘wrongly received’ seamen’s tickets and pilot bills, with the fraud amounting to about £99 – around £7,000 today. [4]

And in November that year, Whitaker had to write again, warning the Navy Board that ‘Leah Wilkinson, daughter of Anne Low[sic] deceased’ was still employing agents to receive money on her behalf, by naming them in forged letters of attorney. This letter shed light on Leah’s criminal habits – she had learned them from her mother Anne.

William Rycroft, a seaman on the Victory ship, had returned to England and gone looking for his owed wages. On him making inquiries, it emerged that in 1692, a false letter of attorney had been honoured, and Anne Lowe had received Rycroft’s wages as a result.

Two years later, Anne Lowe had been paid wages due to Thomas Pettit, a seaman on the Hannibal. Whitaker was rightly concerned that Leah and her agents were continuing their scam, and asked that any requests for power of attorney made by Leah’s agents, a Mr Harmon and an Emeroy Solesby, be stopped until they could be fully examined. [5]

Extract from Richard Burn’s The Justice of the Peace (1776)

on the crimes committed by Leah Wilkinson

(image c/o Nell Darby)

Forgery was an offence both in common law and by statute; at common law, forgery was ‘an offence in falsely and fraudulently making or altering any manner of record, or any other authentic matter of a publick nature; as a will and the like’ [6]. Certain classes of forgery were felonies without benefit of clergy, but luckily for Leah, at the time she committed her crimes, they did not come under this category.

However, the forging of letters of attorney and wills of seamen was recognized as a growing ‘evil practice’ by the end of the 17th century. Legislation was passed in 1697 to tackle the problem.

Not only did the forging of seamen’s letters of attorney become a distinct offence, punishable with a £200 fine – to be split between the king and the prosecutor – and imprisonment until the fine was paid, but the act made it illegal to produce a will AND a letter of attorney for a seaman on the same paper or parchment. If both documents were on the same paper, they would not ‘be good or available in Law to any intent or purpose’. [7]

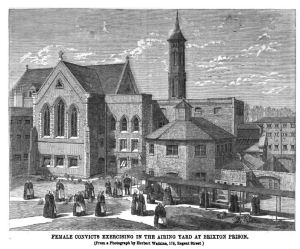

There is no mention of Leah for the next few years, but there is no evidence that she stopped offending – just that, perhaps, she was more careful for a while. But in January 1712, the London Gazette reported that she was up to her old tricks. Describing her as ‘a notorious Old Offender’ – one has to feel a bit of sympathy with her for that epithet – the Navy Office reported that she had just been convicted at the Old Bailey for publishing a forged Bill of Sale or Assignment for the wages of a dead seaman, John Godfrey.

The Navy Pay Office

(from a drawing by G Shepherd, 1816)

Leah was put in the pillory outside here.

She was sentenced to stand on the pillory in front of the Navy Pay Office, which was on the corner of Great Winchester Street and Old Broad Street in London, and to stay in prison for a month. Her conviction and punishment was ‘advertised for deterring others from committing the like Offences’. [8]

But not even a spell in the pillory could stop Leah; presumably she was imprisoned for being unable to pay the statutory fine for her conviction, which suggests that she did not get to profit very much from her crimes. Perhaps, brought up by her mother to forge documents, she was unable, or reluctant, to earn a living any other way.

So in 1727, the last mention of Leah came. She appeared at the Old Bailey on a charge of drawing up a counterfeit order to receive the pay of another dead seaman – William Bar. It was noted at her trial that she ‘was one of those vile Persons, who makes a Practice of drawing up false Powers, and Letters of Administration, and thereby cheating and defrauding the Widows of such Seamen as die in the Voyage.’ This trial report gives us the best picture we have of the elderly Leah, and shows how the court view a forger who was also female.

Leah spoke at her trial in her own defence. The report stated, ‘She pleaded a great deal of Ignorance, Innocence and Incapacity, yet she talk’d of Administrations, Probates, and broad Seals, with as much Dexterity as if she had been educated at Doctor’s Commons.’ [9]

This was a self-educated woman, who, through her long criminal career, had learned a lot about the law and legal process. She played on the stereotypes of womanhood and her age, yet her proudly-displayed knowledge of probate put paid to her claims of ignorance.

Unsurprisingly, the jury found her guilty on this first count, and also on a charge of ‘persuading Margaret Smith to personate and take upon her’ the name of William Bar’s widow, in order to claim the £17 wages that had been due to her after her husband’s death. Leah was again ordered to stand in the Broad Street pillory, and given a longer prison sentence – 12 months, this time. [10]

In the end, Leah’s criminal career was probably curtailed by death rather than repentance; it is likely that she died in 1729, being buried in the non-conformist burial ground at Bunhill Fields. Her career had a negative impact on many seamen’s families; but it is impossible not to feel a little bit of admiration at this woman who learned about the law from a somewhat unconventional perspective.

Nell Darby is a PhD student at the University of Northampton, researching women’s involvement in the summary process during the long eighteenth-century. She blogs at criminalhistorian.com and is on Twitter @nelldarby

FOOTNOTES

1: Old Bailey Proceedings Online, December 1695, trial of Leah Wilkinson (t16951203-35).

2: ‘William III, 1697-8: An Act for the better preventing the imbezlement of His Majesties Stores of War and preventing Cheats Frauds and Abuses in paying Seamens Wage (chapter XLI. Rot. Parl. 9 Gul. III, p.7 n.1)’ in John Raithby (ed), Statutes of the Realm, volume 7: 1695-1701)

3: The National Archives, ref ADM 106/498/126, 11 April 1696

4: The National Archives, ref ADM 106/498/186, 5 June 1696

5: The National Archives, ref ADM 106/497/207, 26 November 1696

6: Richard Burn, The Justice of the Peace, and Parish Officer (13th edition, 1776), Vol 2, p.208

7: 9&10 William III c.41, as detailed in ‘William III, 1697-8: An Act for the better preventing the imbezlement of His Majesties Stores of War and preventing Cheats Frauds and Abuses in paying Seamens Wage (chapter XLI. Rot. Parl. 9 Gul. III, p.7 n.1)’ in John Raithby (ed), Statutes of the Realm, volume 7: 1695-1701)

8: The London Gazette, 20 January 1712

9: Old Bailey Proceedings Online, trial of Leah Wilkinson (t17270412-48), 12 April 1727

10: Old Bailey Proceedings Online, April 1727, punishment summary for Leah Wilkinson (s17270412-1), 12 April 1727